Double-Barreled

By Subhravanu Das

A pandit, his head shaved and his mustache bedecked with dice, once predicted that I would live only till my twenty-ninth birthday and die with my hair at its silkiest best. Of course, had my father donated to the temple exchequer twenty bags of rice instead of ten, the prediction could have been more generous. But due to this half-assery, my life, from that morning on, ran in doubles. I drank double the milk, I read double the books, I was asked to score double the marks. I got singled out by my friends, and I had to double down on the cash I blew on them. I finished engineering before them all and joined a telecom company at half-salary. And when I got married the day I turned twenty-one, I had to bow before double the number of belled elephants any wedding had ever seen.

Of course, it didn't last long. It'”the marriage-agreement, the renegotiation, the sex. How could it? My wife never got the chance to keep up with me. Before she could wake up, I would do the dishes. Before she could finish eating, I would grab the plate out of her hands. Before she could plan a trip for us, I would tour the holy riverbanks, glug the prasads, and return with my unused shoes in our two-faced backpack. 'You're tiring me out,' she would say. I told her to take some time off and go visit her sister. But she hated her family more than I cowered before mine. So she sat cross-legged on our bed and watched me run rings around her. She cut her hair shorter and shorter. The evening she moved out, she gifted me a double-barreled rifle that shot out saffron confetti.

Life eased up once our separation was formalized. In the eyes of all, I had already completed a lifetime. They stopped calling, and I got a sloth tattooed onto my chest. I left my job and crawled to a pet store, where I was informed that sloths make terrible pets. 'They are wild animals and do not seek out human contact.' The store did not have any sloths hanging around for me to verify this assertion. So I went to a zoo and discovered they housed only a sloth bear who appeared slow, but not as much as a sloth. Still, I showed up daily, till the sloth bear raised its legs in pranam in my direction twice, which I understood to be a request to quit intruding. I got a bouquet of leaves tattooed onto my chest so that my sloth could hide in peace and returned home and never stepped out again. The night of the prediction eventually arrived, and I turned twenty-nine with my hair spiraling into a cocoon and my phone ringing nonstop, though I couldn't recollect setting the sound of two thousand conch shells being simultaneously blown as my ringtone.

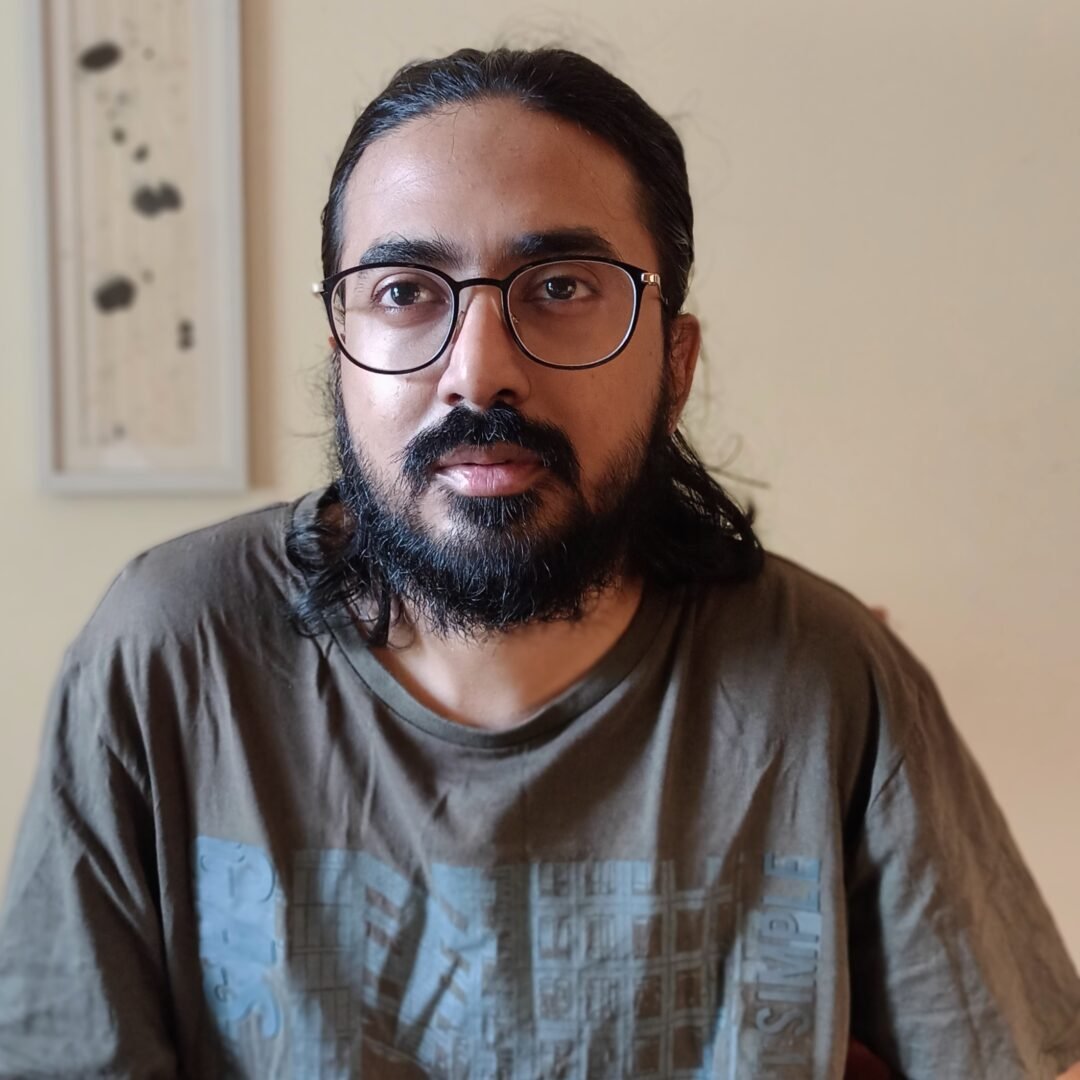

Subhravanu Das is an Indian writer living in Bhubaneswar. His work has been published in Gordon Square Review, Atlas and Alice, Chestnut Review, and AAWW’s The Margins, among others, and included in Wigleaf’s Top 50 and Best Small Fictions.